Indivisible

#Documentary

#Health/Healing

:against the margins

‘Indivisible’ began as an exploration into the nuances of racism. It can manifest in many ways: microaggressions, gas-lighting, bullying. But as the project evolved, I realized how much racism influenced development and realized this project is as much about identity formation as it is about racism.Racism and prejudice are pervasive in our culture. But often times, we think of racism as big traumatic events that one recovers from and eventually moves on from. What many don’t realize is how racism, in its many forms, can affect one’s identity formation so pervasively and insidiously that the person will make themselves a different version of themselves, or even invisible, to protect themselves.

There’s not enough discussion around the effects of racism and systemic racism on a human level. The denial of culture, the assumptions around our bodies, the condescension towards accents, the biases against skin color, and the intergenerational effects all have an effect on identity formation and need to be part of our conversations as we build a culture of anti-racism.

Racism has huge implications on our society, on our culture, on the systems we live in, and on who we become as individuals. While ‘Indivisible’ hints at the Pledge of Allegiance and the political controversy of patriotic traditions, ‘Indivisible’ is also a reference to the identities within each person. While nearly every person has expressed how they have fractured their identities in attempts to assimilate, to belong, or to safeguard themselves somehow, each person is still only one person. Their various identities are interconnected, woven together in an indivisible individual.

At the conclusion of each interview, I ask the participant to describe themselves. For so long, their identity has been affected and shaped by external forces and descriptors that are rooted in power dynamics. This statement allows them to define themselves for themselves: a reclamation.

* If you would like to send a message of gratitude or self-reflection to any of the participants for their stories, please feel free to email me using my contact form and I will make sure they receive your note.

**Big thank you to APIC Spokane for helping to fund portions of this project. If you are an individual or part of an organization that would like to help fund this project, please email me at margaret@margaretalbaugh.com*

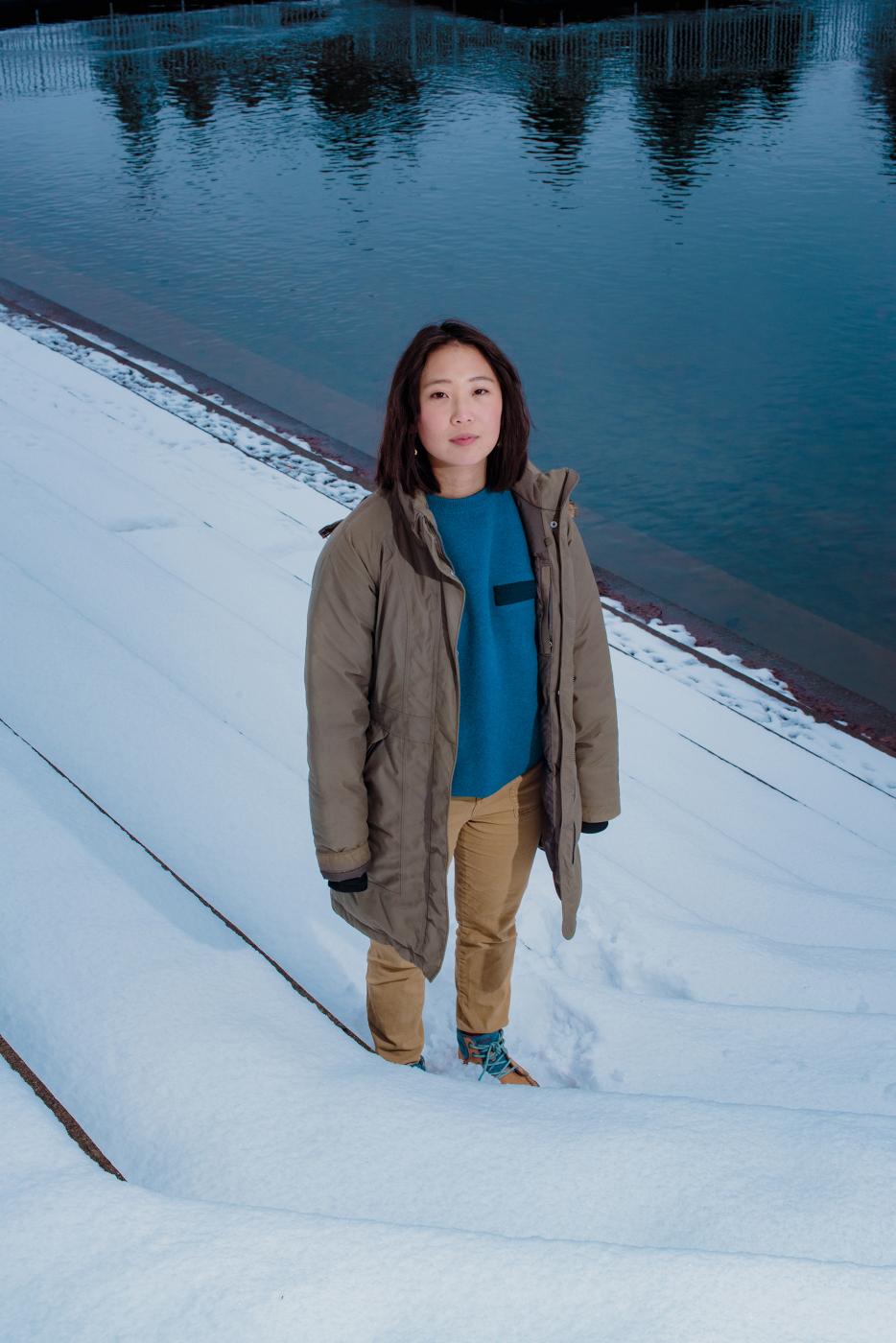

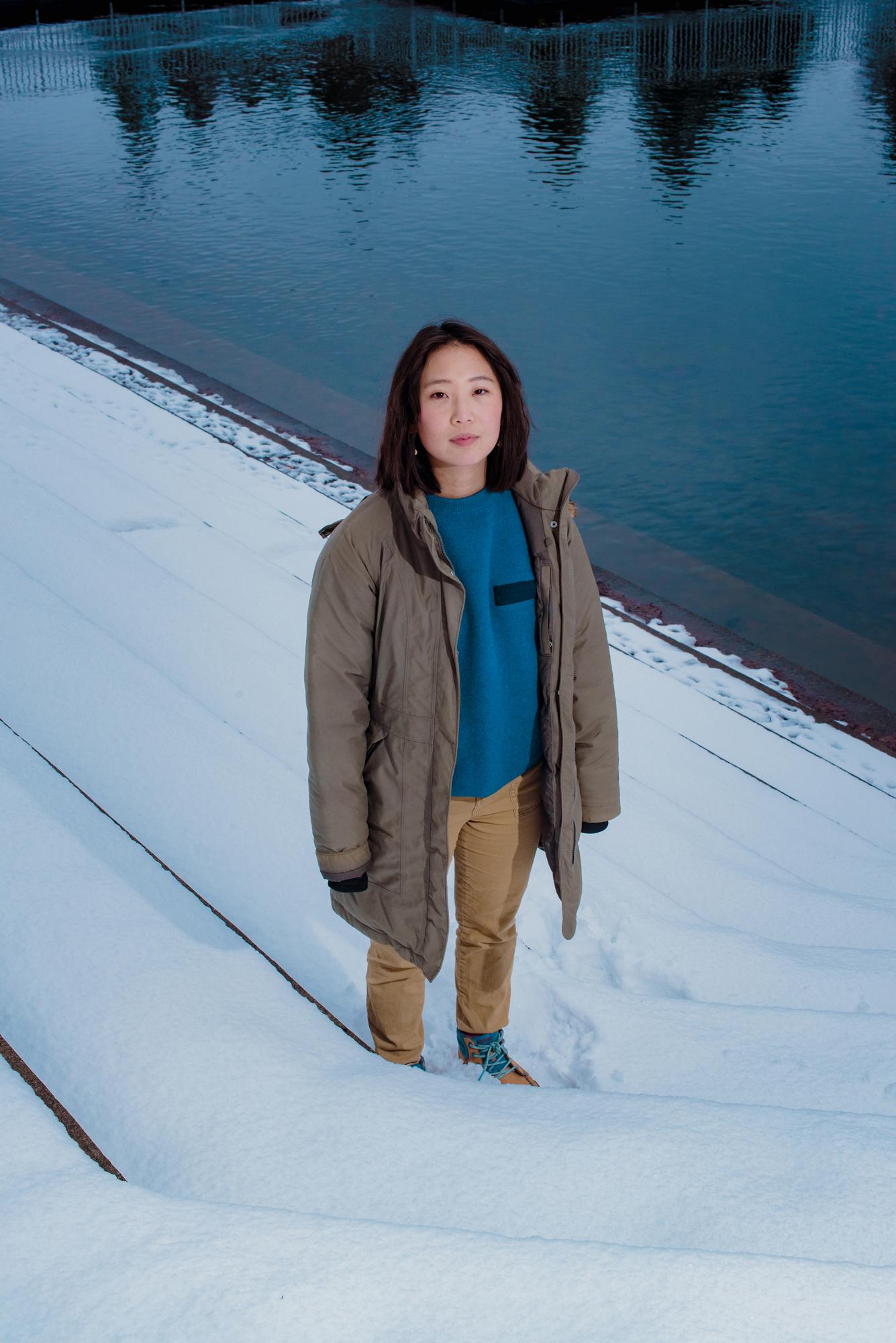

Sooyoun (photographed along the river near her work)

I think part of my struggles with racism feel really insignificant compared to what my parents had to endure, and still continue to endure, because I have English fluency, which is honestly the language of power here. My parents had to learn English mid-life and have a strong accent, they have had to endure a lot of crap from people because people don’t think that they know what they’re talking about. And my mom still asks me to talk in public spaces, even though she’s actually more than proficient in English now. “You, you guys are great at English... You guys order for us.” I'm already more well off in a certain way than my parents. I got to go to college. I graduated from college. I have a job that is nine to five. And my parents still work every day including holidays. And that's not a nine to five. They work at a gas station convenience store type thing. It's just a different world.

There’s millennia of culture to understand what it might mean to be Korean. And there’s hundreds of years of being American. But for the two to come together, there’s nothing. There’s no precedent…There was no space to have that conversation growing up. I never learned about it in school. I never had a teacher that looked like me. Just those kinds of things, right?

There’s a scene in Black Panther I think about often where you see Killmonger as this little boy looking for home and he just can’t figure out where home is. And even though this is a completely different situation, I just felt like he was so relatable in that moment of vulnerability of just trying to figure out where home is. And I see that in myself. But then I also see that in my parents too, who have left their home to be in a place that honestly never welcomed them into their home. So, they don’t really have a home that they feel they truly belong to either, right? And they don’t have many friends here. They left their friends and family back in Korea because there were no jobs. There was a lot of political and economic turmoil in the late 80s and 90s that made them leave. It’s crazy, the Korea we see now and the Korea just 30 years ago – there’s a wild difference. But anyways, I think about that a lot. ‘Home’, and what it means for me, what it means for my parents, and how we’re all still trying to figure out what it means for us.

I am....

…Someone who has … a strong sense of what’s wrong and right.

I love learning and listening to other people.

I think part of my struggles with racism feel really insignificant compared to what my parents had to endure, and still continue to endure, because I have English fluency, which is honestly the language of power here. My parents had to learn English mid-life and have a strong accent, they have had to endure a lot of crap from people because people don’t think that they know what they’re talking about. And my mom still asks me to talk in public spaces, even though she’s actually more than proficient in English now. “You, you guys are great at English... You guys order for us.” I'm already more well off in a certain way than my parents. I got to go to college. I graduated from college. I have a job that is nine to five. And my parents still work every day including holidays. And that's not a nine to five. They work at a gas station convenience store type thing. It's just a different world.

There’s millennia of culture to understand what it might mean to be Korean. And there’s hundreds of years of being American. But for the two to come together, there’s nothing. There’s no precedent…There was no space to have that conversation growing up. I never learned about it in school. I never had a teacher that looked like me. Just those kinds of things, right?

There’s a scene in Black Panther I think about often where you see Killmonger as this little boy looking for home and he just can’t figure out where home is. And even though this is a completely different situation, I just felt like he was so relatable in that moment of vulnerability of just trying to figure out where home is. And I see that in myself. But then I also see that in my parents too, who have left their home to be in a place that honestly never welcomed them into their home. So, they don’t really have a home that they feel they truly belong to either, right? And they don’t have many friends here. They left their friends and family back in Korea because there were no jobs. There was a lot of political and economic turmoil in the late 80s and 90s that made them leave. It’s crazy, the Korea we see now and the Korea just 30 years ago – there’s a wild difference. But anyways, I think about that a lot. ‘Home’, and what it means for me, what it means for my parents, and how we’re all still trying to figure out what it means for us.

I am....

…Someone who has … a strong sense of what’s wrong and right.

I love learning and listening to other people.

Elliotte (photographed by a creek near a hiking trail)

I remember quite vividly my sister had brought Chinese food for her lunch at school and someone had made fun of her and said it looked like a shell. They said, “Janie’s eating shells”. And another person made fun of her last name. So, I was pretty mad about that. “You better not be saying that stuff to my sister!” Our parents went in to go talk to the teacher about it. I was there too; it was after school. And I just remember her coming home from school asking my parents not to pack that stuff for her lunch anymore and that’s how we found out about it.

I told her there’s nothing to be ashamed of, it’s part of our culture and he doesn’t have a right to make of it. Both my parents told her the same things. My grandparents ended up finding out about the story too and told us the same thing – Don’t be ashamed.

I just felt like so mad. I didn’t want them to do it again. I told Janie if she experiences this again, she can always come to me and not to be afraid to tell Mom or Dad and talk to the teacher about it. It isn’t something that should be ignored.

Because of the Asian hate from COVID, I think a couple of Janie’s classmates commented on that too. And Janie said, “No, that’s not okay to say stuff like that”, and I was really proud of her for doing that.

I am…

Creative. That’s probably one of the biggest things because I like to write.

I feel like I’m a friend to everyone. I try to be nice and I like to stand up to people who I think are doing wrong things.

I remember quite vividly my sister had brought Chinese food for her lunch at school and someone had made fun of her and said it looked like a shell. They said, “Janie’s eating shells”. And another person made fun of her last name. So, I was pretty mad about that. “You better not be saying that stuff to my sister!” Our parents went in to go talk to the teacher about it. I was there too; it was after school. And I just remember her coming home from school asking my parents not to pack that stuff for her lunch anymore and that’s how we found out about it.

I told her there’s nothing to be ashamed of, it’s part of our culture and he doesn’t have a right to make of it. Both my parents told her the same things. My grandparents ended up finding out about the story too and told us the same thing – Don’t be ashamed.

I just felt like so mad. I didn’t want them to do it again. I told Janie if she experiences this again, she can always come to me and not to be afraid to tell Mom or Dad and talk to the teacher about it. It isn’t something that should be ignored.

Because of the Asian hate from COVID, I think a couple of Janie’s classmates commented on that too. And Janie said, “No, that’s not okay to say stuff like that”, and I was really proud of her for doing that.

I am…

Creative. That’s probably one of the biggest things because I like to write.

I feel like I’m a friend to everyone. I try to be nice and I like to stand up to people who I think are doing wrong things.

Erina (an animal lover, photographed with her dog)

When I went back to Japan as a college student, the colorism was crazy. Now, all the advertisements were white people. And Disney princesses were all white. I found myself trying to make my eyes bigger with makeup. When we went to Disneyland, I remember my mom commenting on how these characters had small faces. And my two reactions when I see a picture of myself are, Oh, I wish I was skinnier. And Wow, I look so Asian. I think I’m over trying to go for these white beauty standards now.

When I got to undergrad, I started to share some of these things. The group I was involved in, the Christian Fellowship – I’ve always been involved with the church but that’s also been difficult and I’m glad I learned about the colonial history of Christianity – but the chapter focused a lot on racial justice or like ethnic identity and at the time I was like, Oh, wow, this is a pretty unexplored area. But the more I explore it, the more powerful or the more I'm able to find confidence in who I am. There was this organization was called InterVarsity. They would have Asian American conferences, and at Whitman there would also be a POC space or an API space. It was in those places where I found solidarity or common experience, a space where I feel like I could be more authentic. And there's just not a lot of spaces to do that. For example, in med school there's very little space to talk about it. It's super easy just to get caught up in med school because everyone is in the fire hose experience where, especially in your first and second year, you get blasted with so much information. But if we're all experiencing that… I've had to compartmentalize those things and act just like a med student during med school. So yeah, I think just talking about these experiences, and listening, hearing others, seeing others, it's both reassuring and it re-confirms again and again that racism is a huge issue.

I am….

Asian American. Relatively chill but when I’m stressed, I’m not that chill. And I think I can be kind and thoughtful but when I have a lot of thoughts in my head, I’m not really paying attention. And I try to be honest, honest as possible.

Friends describe me as authentic.

When I went back to Japan as a college student, the colorism was crazy. Now, all the advertisements were white people. And Disney princesses were all white. I found myself trying to make my eyes bigger with makeup. When we went to Disneyland, I remember my mom commenting on how these characters had small faces. And my two reactions when I see a picture of myself are, Oh, I wish I was skinnier. And Wow, I look so Asian. I think I’m over trying to go for these white beauty standards now.

When I got to undergrad, I started to share some of these things. The group I was involved in, the Christian Fellowship – I’ve always been involved with the church but that’s also been difficult and I’m glad I learned about the colonial history of Christianity – but the chapter focused a lot on racial justice or like ethnic identity and at the time I was like, Oh, wow, this is a pretty unexplored area. But the more I explore it, the more powerful or the more I'm able to find confidence in who I am. There was this organization was called InterVarsity. They would have Asian American conferences, and at Whitman there would also be a POC space or an API space. It was in those places where I found solidarity or common experience, a space where I feel like I could be more authentic. And there's just not a lot of spaces to do that. For example, in med school there's very little space to talk about it. It's super easy just to get caught up in med school because everyone is in the fire hose experience where, especially in your first and second year, you get blasted with so much information. But if we're all experiencing that… I've had to compartmentalize those things and act just like a med student during med school. So yeah, I think just talking about these experiences, and listening, hearing others, seeing others, it's both reassuring and it re-confirms again and again that racism is a huge issue.

I am….

Asian American. Relatively chill but when I’m stressed, I’m not that chill. And I think I can be kind and thoughtful but when I have a lot of thoughts in my head, I’m not really paying attention. And I try to be honest, honest as possible.

Friends describe me as authentic.

Felicia (photographed near her late dog’s favorite spot in the yard)

I think it was a life skill to be very adaptable. In high school, I was very adaptable to different social situations. I remember having an ex-boyfriend call me a chameleon because I just kept changing in the different situations. He was right. Like I could see people that I dated, they were different individuals, but I was very much like, whatever they liked, I will find a way to be interested in their passion. And it wasn't until I went to university that I slowly started to define my own identity. And what that meant, including what it was to be Chinese.

I decided I was going to choose geology as a major, which was a departure from wanting to be a doctor, or something of a prestigious career choice. Choosing that was also interesting because little did I know, going into mining meant being in a community of white, male, older males, usually. The mining industry is all about

colonialism and patriarchy. Very specific sexism happens in there, and also racism within Canada, and the way they make choices when working with the indigenous

communities. The narrative that comes through is often stereotyping. “The so-and-so that we have to employ meets a certain percentage of what is required of us to do (for our projects),” and, “Don't expect them to show up for the job, because that's just how they are, they're unreliable.” And very dehumanizing comments that I inherited from a lot of the mining male folks on what to expect when working with First Nations. I didn't really recognize these stereotypes as such until probably the last five years. I really

immersed myself into books and education, and talking to people [to unlearn these things].

Also realizing, I think, as a parent, that there's this perspective and this responsibility I have to teach my children so they are aware. I had no one telling me that was wrong, that was not the kind of way we should be treating other human beings because they look different. So, it's both sides - I experienced racism, but I also perpetuated it in the work that I did, or the things I was taught or not taught. So it's finding my way through that, giving my children the opportunity for open communication.

I am....

Chinese. Born in Malaysia. Immigrant to Canada. Even saying that is uncomfortable for me because Canada is a colonial name. The First Nations refer to it as Turtle Island. I’m a work in progress. And an empath. And I’m sensitive.... and still evolving.

I think it was a life skill to be very adaptable. In high school, I was very adaptable to different social situations. I remember having an ex-boyfriend call me a chameleon because I just kept changing in the different situations. He was right. Like I could see people that I dated, they were different individuals, but I was very much like, whatever they liked, I will find a way to be interested in their passion. And it wasn't until I went to university that I slowly started to define my own identity. And what that meant, including what it was to be Chinese.

I decided I was going to choose geology as a major, which was a departure from wanting to be a doctor, or something of a prestigious career choice. Choosing that was also interesting because little did I know, going into mining meant being in a community of white, male, older males, usually. The mining industry is all about

colonialism and patriarchy. Very specific sexism happens in there, and also racism within Canada, and the way they make choices when working with the indigenous

communities. The narrative that comes through is often stereotyping. “The so-and-so that we have to employ meets a certain percentage of what is required of us to do (for our projects),” and, “Don't expect them to show up for the job, because that's just how they are, they're unreliable.” And very dehumanizing comments that I inherited from a lot of the mining male folks on what to expect when working with First Nations. I didn't really recognize these stereotypes as such until probably the last five years. I really

immersed myself into books and education, and talking to people [to unlearn these things].

Also realizing, I think, as a parent, that there's this perspective and this responsibility I have to teach my children so they are aware. I had no one telling me that was wrong, that was not the kind of way we should be treating other human beings because they look different. So, it's both sides - I experienced racism, but I also perpetuated it in the work that I did, or the things I was taught or not taught. So it's finding my way through that, giving my children the opportunity for open communication.

I am....

Chinese. Born in Malaysia. Immigrant to Canada. Even saying that is uncomfortable for me because Canada is a colonial name. The First Nations refer to it as Turtle Island. I’m a work in progress. And an empath. And I’m sensitive.... and still evolving.

Janie (photographed with her favorite chicken)

So, this Indian boy in my class, he thinks racism is bad obviously. We started just talking COVID or something like that. And he said COVID was all the Chinese’s fault. And all the girls that were near him all turned around and like told him that was bad.

And apparently my teacher did not hear even though he practically yelled it so I told her I told our teacher and she said she would talk to him.

I was made fun of for the char siu bao I was eating for lunch once. A kid in my class said, “Your lunch looks like a shell! Janie’s eating a shell!” When I got home, I told my parents what had happened. My parents said I shouldn’t be embarassed. This food is part of my culture. And just like my class values say, Treat others how you want to be treated: with kindness and respect.

I am....

Kind. Smart. Not too much of a risk-taker, I wouldn’t jump off a cliff into the water. Sensible. Knowledgeable. A lot of things I don’t have the words to describe.

So, this Indian boy in my class, he thinks racism is bad obviously. We started just talking COVID or something like that. And he said COVID was all the Chinese’s fault. And all the girls that were near him all turned around and like told him that was bad.

And apparently my teacher did not hear even though he practically yelled it so I told her I told our teacher and she said she would talk to him.

I was made fun of for the char siu bao I was eating for lunch once. A kid in my class said, “Your lunch looks like a shell! Janie’s eating a shell!” When I got home, I told my parents what had happened. My parents said I shouldn’t be embarassed. This food is part of my culture. And just like my class values say, Treat others how you want to be treated: with kindness and respect.

I am....

Kind. Smart. Not too much of a risk-taker, I wouldn’t jump off a cliff into the water. Sensible. Knowledgeable. A lot of things I don’t have the words to describe.

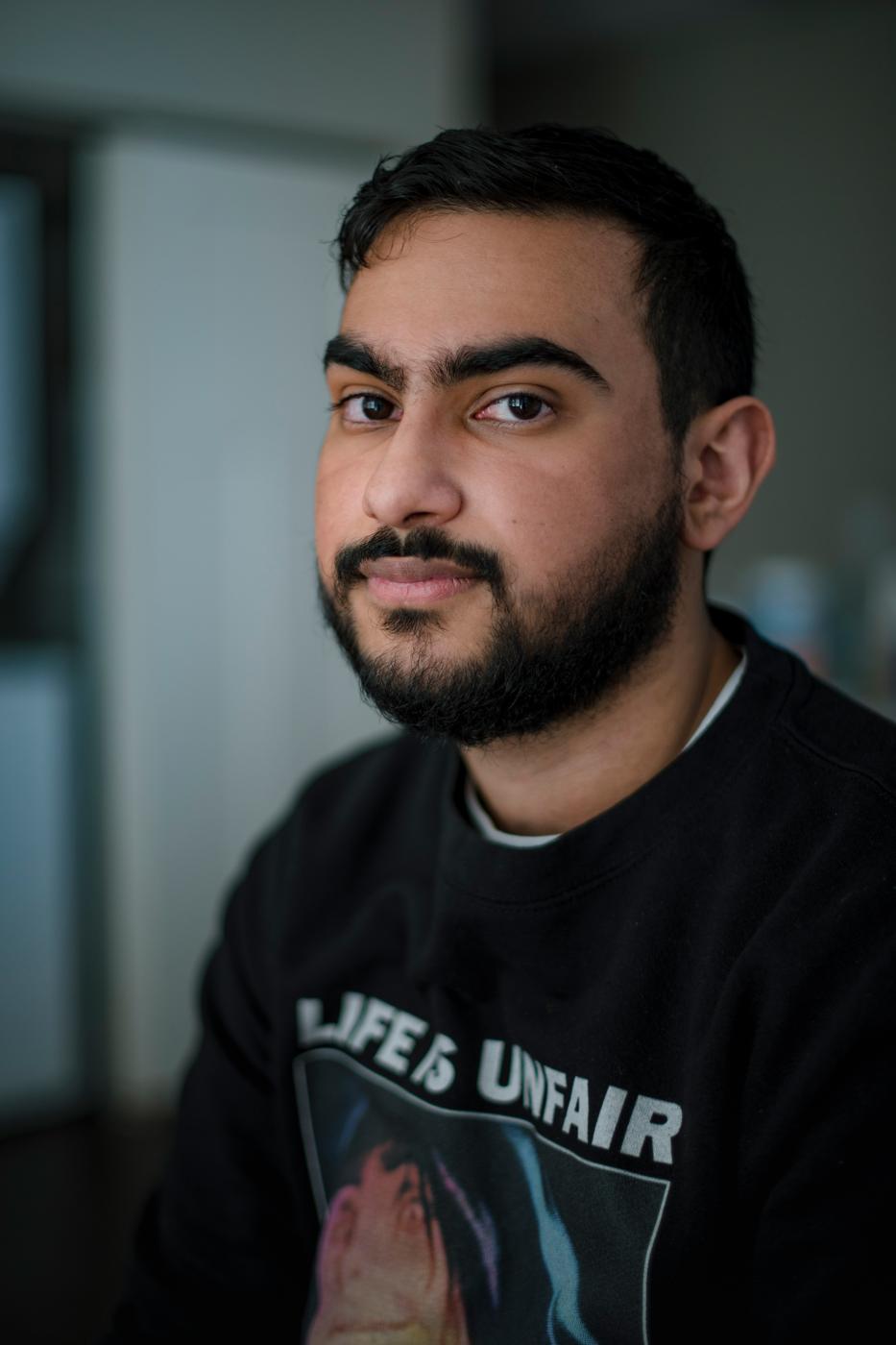

Pavandeep (photographed in his apartment)

I remember there was this kid, he would find a stick every day. He would poke me and when I would say something, he would say, “Oh Pav, he’s going to blow up.” And then this kid once asked me in front of the whole class if I celebrated 9/11 which put me in the awkward position of saying, ‘Yeah, cause it’s my dad’s birthday’.

I was thinking about this the other day. Kids my generation, we wanted to be white. When you’re 7, 8, 9 you want to be part of the group. You want to be the same. So, you’re always observing – I’m not being treated the same, black kids aren’t being treated the same, Asians aren’t being treated the same. The white kids – that’s ‘normal’. That is what we convince ourselves as normal. So, growing up wanting to be white, we experience through that lens. For example, I was always hesitant to invite kids over. They might hear my dad speak, hear his accent, and automatically equate that to Apu from the Simpsons. That’s something you could get made fun of for. My mom would pack my lunches and kids would say, ‘Ew, what’s that smell?’ Stuff like that limits your interactions. You don’t want them to see your ‘otherness’.

It’s a shame that we’re never allowed to be comfortable with our own identities and that leads to an identity crisis. Growing up, I’m not white, obviously. I’m not black. And the word ‘Asian’ was hard as an Indian because in America there is an association with East Asia. So, it’s tough to come to grips with the fact it takes a lot of effort to identify with a certain group and own that identity while at the same time cultivating your own individual identity.

I am...

I’m Punjabi. I’m more comfortable identifying with that than ethnicity. I’m an

American. I’m way more comfortable identifying as American now than I used to be.

A passion of mine is helping people. I was always the empathetic kid and that has

manifested into my career [as a counselor]. I hope to go back to my hometown and spread awareness in minority communities. And it all goes back to the fact that it’s okay to be different.

I remember there was this kid, he would find a stick every day. He would poke me and when I would say something, he would say, “Oh Pav, he’s going to blow up.” And then this kid once asked me in front of the whole class if I celebrated 9/11 which put me in the awkward position of saying, ‘Yeah, cause it’s my dad’s birthday’.

I was thinking about this the other day. Kids my generation, we wanted to be white. When you’re 7, 8, 9 you want to be part of the group. You want to be the same. So, you’re always observing – I’m not being treated the same, black kids aren’t being treated the same, Asians aren’t being treated the same. The white kids – that’s ‘normal’. That is what we convince ourselves as normal. So, growing up wanting to be white, we experience through that lens. For example, I was always hesitant to invite kids over. They might hear my dad speak, hear his accent, and automatically equate that to Apu from the Simpsons. That’s something you could get made fun of for. My mom would pack my lunches and kids would say, ‘Ew, what’s that smell?’ Stuff like that limits your interactions. You don’t want them to see your ‘otherness’.

It’s a shame that we’re never allowed to be comfortable with our own identities and that leads to an identity crisis. Growing up, I’m not white, obviously. I’m not black. And the word ‘Asian’ was hard as an Indian because in America there is an association with East Asia. So, it’s tough to come to grips with the fact it takes a lot of effort to identify with a certain group and own that identity while at the same time cultivating your own individual identity.

I am...

I’m Punjabi. I’m more comfortable identifying with that than ethnicity. I’m an

American. I’m way more comfortable identifying as American now than I used to be.

A passion of mine is helping people. I was always the empathetic kid and that has

manifested into my career [as a counselor]. I hope to go back to my hometown and spread awareness in minority communities. And it all goes back to the fact that it’s okay to be different.

Remelisa (photographed in her home and studio space)

I remember going to those parties and seeing a lot of folks who looked like my cousins, my mom, and my Titos, and my Titas. Like, they all looked very familiar and that was nice, but I always felt like an outsider. I don't know any Tagalog. I can't speak any other language other than English, and it makes me feel very deficient. So, I was always left out of conversations when I was at those parties. I wasn't really in the

cultural know. Because all I know is growing up and being raised here.

In elementary school I had maybe two Asian classmates, and one was from kindergarten until second grade and then the other one was from fourth grade until sixth grade. At some point in school I had that moment of Oh, I really am different. I think it was a math lesson with how many kids have blue eyes versus how many had brown eyes. I looked around going, Wait, we’re the only ones with brown eyes? This, this is telling.

When I was younger I used to say a lot of racist jokes because I thought that was what you had to do to assimilate and to make people feel comfortable. For so long, I catered to other people’s comforts. For a long time, I went by the nickname Remi in school because teachers, substitute teachers, other students had a hard time remembering my name. Just generally, “Remelisa is a mouthful,” and I thought, Is it?

I am....

a very creative and thoughtful person who just wants everyone to be open to listening to other people’s stories but be able to share their stories too. And I think one of the most important ways to share stories is through a creative expression. Whether it’s

stories or emotions. And crazy cat person.

I remember going to those parties and seeing a lot of folks who looked like my cousins, my mom, and my Titos, and my Titas. Like, they all looked very familiar and that was nice, but I always felt like an outsider. I don't know any Tagalog. I can't speak any other language other than English, and it makes me feel very deficient. So, I was always left out of conversations when I was at those parties. I wasn't really in the

cultural know. Because all I know is growing up and being raised here.

In elementary school I had maybe two Asian classmates, and one was from kindergarten until second grade and then the other one was from fourth grade until sixth grade. At some point in school I had that moment of Oh, I really am different. I think it was a math lesson with how many kids have blue eyes versus how many had brown eyes. I looked around going, Wait, we’re the only ones with brown eyes? This, this is telling.

When I was younger I used to say a lot of racist jokes because I thought that was what you had to do to assimilate and to make people feel comfortable. For so long, I catered to other people’s comforts. For a long time, I went by the nickname Remi in school because teachers, substitute teachers, other students had a hard time remembering my name. Just generally, “Remelisa is a mouthful,” and I thought, Is it?

I am....

a very creative and thoughtful person who just wants everyone to be open to listening to other people’s stories but be able to share their stories too. And I think one of the most important ways to share stories is through a creative expression. Whether it’s

stories or emotions. And crazy cat person.

Rowena (photographed in her home)

I think when I was younger, especially as an immigrant moving to the States, you try to minimize your racial identity as much as possible. Because you just want to belong. That's what it is: desire to belong, and so you're going to minimize the characteristics that makes you stand out. I've done that. I think for me, knowing English coming into the country - it impacted my relationship with my father. Because as a child, even though I knew English coming in, I also picked it up much faster. And so, there's a little bit of a role reversal that happens when you can speak the language of the dominant society. I would have to translate for my dad. I would be doing some of his legal forms, applications, whatever, because I could understand that better than he could. That changes some of that dynamic within the parent-child relationships. That's an interesting dynamic that happens when kids immigrate to the US at a younger age, and the role that they take in the house. I think that also contributes to some of that internalized racism and oppression because you're, like, “You should be doing this yourself, instead of me having to do that”. When you're hearing in the mainstream that the narrative is that ‘Asians sound dumb’ or ‘immigrants are dumb’, and then you're having to take care of your parents – it really reinforces something to you about that narrative. Just a little bit. And then you're getting the messages that the language that your parents speak isn't valued at all just adds to it.

I think the other thing that happens, when you move to the United States and there are languages that are valued more than others, in terms of foreign languages, you end up moving away from - or I ended up moving away from - Tagalog. In high school, your choices of foreign languages to take did not include that. Nor is it acknowledged that you're already speaking at least two languages, already bilingual. But to the eyes of many, that's not the bilingual they want. It's Spanish, French, German, Latin. It's not until recently that Mandarin stuck much more at the forefront. And so that's also what we internalize. Yes, I speak this language, but it's not as valuable as these other languages. So, my culture must be less than these others.

I am…

Asian American. I describe myself as 1.5 generation – in between the first generation being the immigrant generation and the second generation being born here. The 1.5 generation is those who came here young enough that you’re in between. I also find myself grounding that identity to the broader history and context of my family members who influenced me. So, part of my identity is having a grandmother who came from a family where women play a very big role.

I think when I was younger, especially as an immigrant moving to the States, you try to minimize your racial identity as much as possible. Because you just want to belong. That's what it is: desire to belong, and so you're going to minimize the characteristics that makes you stand out. I've done that. I think for me, knowing English coming into the country - it impacted my relationship with my father. Because as a child, even though I knew English coming in, I also picked it up much faster. And so, there's a little bit of a role reversal that happens when you can speak the language of the dominant society. I would have to translate for my dad. I would be doing some of his legal forms, applications, whatever, because I could understand that better than he could. That changes some of that dynamic within the parent-child relationships. That's an interesting dynamic that happens when kids immigrate to the US at a younger age, and the role that they take in the house. I think that also contributes to some of that internalized racism and oppression because you're, like, “You should be doing this yourself, instead of me having to do that”. When you're hearing in the mainstream that the narrative is that ‘Asians sound dumb’ or ‘immigrants are dumb’, and then you're having to take care of your parents – it really reinforces something to you about that narrative. Just a little bit. And then you're getting the messages that the language that your parents speak isn't valued at all just adds to it.

I think the other thing that happens, when you move to the United States and there are languages that are valued more than others, in terms of foreign languages, you end up moving away from - or I ended up moving away from - Tagalog. In high school, your choices of foreign languages to take did not include that. Nor is it acknowledged that you're already speaking at least two languages, already bilingual. But to the eyes of many, that's not the bilingual they want. It's Spanish, French, German, Latin. It's not until recently that Mandarin stuck much more at the forefront. And so that's also what we internalize. Yes, I speak this language, but it's not as valuable as these other languages. So, my culture must be less than these others.

I am…

Asian American. I describe myself as 1.5 generation – in between the first generation being the immigrant generation and the second generation being born here. The 1.5 generation is those who came here young enough that you’re in between. I also find myself grounding that identity to the broader history and context of my family members who influenced me. So, part of my identity is having a grandmother who came from a family where women play a very big role.

Ryan (photographed in front of the Hawaiian flag that hangs in his living room)

There are still those people in the world who have no idea – no idea what it’s like to be consistently put down, consistently looked at like Why are you here?And being proud of who I am is a slap in the face to them. I’m not allowed to be Hawaiian.

Normally when I tell people I’m Hawaiian, people say, “Hawaii is the 50th state.” But it all started with western colonization. It started from oppression.

And when I say that, people say, “Go back then. Go back to where you’re from.” And I think, “Well, you guys should leave first.” I ain’t going anywhere. We were here first. But that’s always the remark I get when I tell people I’m Hawaiian. “Go back home”.

My parents are ones who say they’re American. Their generation, they’re the lost generation. My grandparents, (my dad’s parents), they spoke Hawaiian. They lived the Hawaiian culture. But my Parents were born in a time period where the language was illegal to speak. It was illegal in schools and you would get beat almost if you were willing to speak your language. That’s the time period my parents were raised. Hawaii become a state in 1959, my dad was born in 1960, and my mom was born in 1964. And during the 1970s, that was when the resurgence of Hawaiian culture and Hawaiian revitalization was coming about. My parents were raised in the public school system and they knew nothing about Hawaiian culture.

In my family, it’s me, my mom, and my dad. And not being able to speak the language – it hurts. I do practice here and there. My girlfriend and I try to incorporate it because, just like anything, if you don’t use it you lose it. We might not use large sentence structures or have general conversations, but just utilizing words triggers something in our brain.

I am....

...pretty outgoing. Charismatic. Loving. Quiet at times. I think a lot of people see what I portray to them. But I’m quiet, insecure, hard-headed. Stubborn. One-track minded. I think I do things for myself but also for others to make people happy, to be filled with love cause not everyone has that. Everyone deserves to have love, compassion and understanding. When I think of myself as who I am, who I see in the mirror, I’m kānaka maoli, I’m Hawaiian until the day I die.

There are still those people in the world who have no idea – no idea what it’s like to be consistently put down, consistently looked at like Why are you here?And being proud of who I am is a slap in the face to them. I’m not allowed to be Hawaiian.

Normally when I tell people I’m Hawaiian, people say, “Hawaii is the 50th state.” But it all started with western colonization. It started from oppression.

And when I say that, people say, “Go back then. Go back to where you’re from.” And I think, “Well, you guys should leave first.” I ain’t going anywhere. We were here first. But that’s always the remark I get when I tell people I’m Hawaiian. “Go back home”.

My parents are ones who say they’re American. Their generation, they’re the lost generation. My grandparents, (my dad’s parents), they spoke Hawaiian. They lived the Hawaiian culture. But my Parents were born in a time period where the language was illegal to speak. It was illegal in schools and you would get beat almost if you were willing to speak your language. That’s the time period my parents were raised. Hawaii become a state in 1959, my dad was born in 1960, and my mom was born in 1964. And during the 1970s, that was when the resurgence of Hawaiian culture and Hawaiian revitalization was coming about. My parents were raised in the public school system and they knew nothing about Hawaiian culture.

In my family, it’s me, my mom, and my dad. And not being able to speak the language – it hurts. I do practice here and there. My girlfriend and I try to incorporate it because, just like anything, if you don’t use it you lose it. We might not use large sentence structures or have general conversations, but just utilizing words triggers something in our brain.

I am....

...pretty outgoing. Charismatic. Loving. Quiet at times. I think a lot of people see what I portray to them. But I’m quiet, insecure, hard-headed. Stubborn. One-track minded. I think I do things for myself but also for others to make people happy, to be filled with love cause not everyone has that. Everyone deserves to have love, compassion and understanding. When I think of myself as who I am, who I see in the mirror, I’m kānaka maoli, I’m Hawaiian until the day I die.

Ryann (photographed at a favorite eatery surrounded by reflections)

I think I realized the world around me didn’t make it easy for me to express myself or be who I feel like I'm growing into. So, I keep thinking of ways to change it so that, not just me, but anyone can feel like this place is accepting of them. So they can reach their potential, or that there even is potential.

I can recognize how my family grew up in a time where they weren’t widely accepted for being Asian and they struggled to fit in or had to go through name calling. The women in my family were fetishized and it carried down through generational trauma. My parents tried to protect me. But this also had its negative points.

With my gender and sexuality – I never paid much attention to how I felt. I just saw love as coming from other people and not from myself. Because I didn’t have examples of non-binary people in my life – there were only gay or lesbian and not any transgender people. And even the people on TV who cross dressed – they were portrayed as comedic relief or weirdos. And it’s the same as Asian people in media – they weren’t ever the main character and didn’t have much substance. They were only portrayed one way. I think of how there were only so few examples I could draw from to really understand myself. I just continued to exist in the world as parts of other people. And I think none of those parts became who I felt I really was.

And then I met another non-binary person and it felt like I could really own that identity. It made sense to me I am non-binary cause I never felt I never fully subscribed to the way the gender binary works. I think that [intersects] with racism and how having another marginalized identity – being queer and non-binary – leaves me open to more vulnerabilities. I upheld those fears in myself though I hardly come across people that are hateful to me directly. I know those people exist and it is scary thinking of this conflict I might face. And I think that’s because my parents made me pretty fearful of the world because my mom lived a life of fear as well, being an Asian woman in the 60s and 70s where there was a lot more racism. She just wanted to protect me and my

brother.

I am…

I don't know why, it's hard for me to just admit that maybe I'm cool.

Or like multi-talented, smart, compassionate.

I am someone's partner. Cat parent, hardworking, fun sometimes.

I think I realized the world around me didn’t make it easy for me to express myself or be who I feel like I'm growing into. So, I keep thinking of ways to change it so that, not just me, but anyone can feel like this place is accepting of them. So they can reach their potential, or that there even is potential.

I can recognize how my family grew up in a time where they weren’t widely accepted for being Asian and they struggled to fit in or had to go through name calling. The women in my family were fetishized and it carried down through generational trauma. My parents tried to protect me. But this also had its negative points.

With my gender and sexuality – I never paid much attention to how I felt. I just saw love as coming from other people and not from myself. Because I didn’t have examples of non-binary people in my life – there were only gay or lesbian and not any transgender people. And even the people on TV who cross dressed – they were portrayed as comedic relief or weirdos. And it’s the same as Asian people in media – they weren’t ever the main character and didn’t have much substance. They were only portrayed one way. I think of how there were only so few examples I could draw from to really understand myself. I just continued to exist in the world as parts of other people. And I think none of those parts became who I felt I really was.

And then I met another non-binary person and it felt like I could really own that identity. It made sense to me I am non-binary cause I never felt I never fully subscribed to the way the gender binary works. I think that [intersects] with racism and how having another marginalized identity – being queer and non-binary – leaves me open to more vulnerabilities. I upheld those fears in myself though I hardly come across people that are hateful to me directly. I know those people exist and it is scary thinking of this conflict I might face. And I think that’s because my parents made me pretty fearful of the world because my mom lived a life of fear as well, being an Asian woman in the 60s and 70s where there was a lot more racism. She just wanted to protect me and my

brother.

I am…

I don't know why, it's hard for me to just admit that maybe I'm cool.

Or like multi-talented, smart, compassionate.

I am someone's partner. Cat parent, hardworking, fun sometimes.

Tiffany (photographed at the beach vacationing with her family)

There was someone in the street who yelled, “Go back to your country!” I remember thinking, “This is my country…” I think I was 11 years old.

I think I grew up with so much shame around being Chinese because when I was little people would pull their eyes and say stupid stuff, and always ask me why my English was so good. And one time I threw away my lunch because I was ashamed that I had Chinese food and to this day I regret it and I should say sorry to my parents. Because that is a big thing in Chinese culture – you don't waste food, ever. To throw it away was very bad.

I don't think there was an obvious or specific time when a white person said to me, “I'm better than you,” but me feeling inferior is something I've internalized my whole life. Where did this idea come from? Maybe it's because all the movies and stories were about them and I read their history so I think I just always thought, Oh, I need to fit into this piece of the world that I landed in. I was born in America but maybe I'm supposed to play a supporting role in this bigger narrative of who Americans are and I'm just fortunate to be part of the diversity of it. It's really interesting because I think it's just so, so subtle that we don't really know how this happens. Because even Allen would tell me when we were dating, “I feel like you deserve to be with a white person, like someone better than me”, and I was like, “Allen, there's no one better than you!” For my friends who dated white people, I would think "Oh, you landed a white guy! Oh, you're better! You dated outside our culture, you transcended our culture.... You did better." But now, I don't think that anymore.

I am....

now I say I'm a third generation Chinese American based in Los Angeles. I think including Chinese American is an important part of my identity because for so long, we wanted to have this colorblind cartoon and be like, "people are people." And now I don't think there's anything wrong with saying where you came from 1) so that no one has to ask you what you are. And 2) because it's okay to say that. It carries meaning. By claiming Chinese American as part of my identity, it gives people an opportunity to know me as an individual that they can place along with all their other ideas about who Chinese American people are. I think that helps sometimes for cultures not to be monoliths anymore. I'm hopeful, thoughtful, caring, creative, (which is a word that I couldn't own for a long time, almost like I needed other people to tell me that I was creative). It was almost a badge of honor that I couldn't wear unless someone else put it on me. I’m spiritual, a good friend, a good listener.

There was someone in the street who yelled, “Go back to your country!” I remember thinking, “This is my country…” I think I was 11 years old.

I think I grew up with so much shame around being Chinese because when I was little people would pull their eyes and say stupid stuff, and always ask me why my English was so good. And one time I threw away my lunch because I was ashamed that I had Chinese food and to this day I regret it and I should say sorry to my parents. Because that is a big thing in Chinese culture – you don't waste food, ever. To throw it away was very bad.

I don't think there was an obvious or specific time when a white person said to me, “I'm better than you,” but me feeling inferior is something I've internalized my whole life. Where did this idea come from? Maybe it's because all the movies and stories were about them and I read their history so I think I just always thought, Oh, I need to fit into this piece of the world that I landed in. I was born in America but maybe I'm supposed to play a supporting role in this bigger narrative of who Americans are and I'm just fortunate to be part of the diversity of it. It's really interesting because I think it's just so, so subtle that we don't really know how this happens. Because even Allen would tell me when we were dating, “I feel like you deserve to be with a white person, like someone better than me”, and I was like, “Allen, there's no one better than you!” For my friends who dated white people, I would think "Oh, you landed a white guy! Oh, you're better! You dated outside our culture, you transcended our culture.... You did better." But now, I don't think that anymore.

I am....

now I say I'm a third generation Chinese American based in Los Angeles. I think including Chinese American is an important part of my identity because for so long, we wanted to have this colorblind cartoon and be like, "people are people." And now I don't think there's anything wrong with saying where you came from 1) so that no one has to ask you what you are. And 2) because it's okay to say that. It carries meaning. By claiming Chinese American as part of my identity, it gives people an opportunity to know me as an individual that they can place along with all their other ideas about who Chinese American people are. I think that helps sometimes for cultures not to be monoliths anymore. I'm hopeful, thoughtful, caring, creative, (which is a word that I couldn't own for a long time, almost like I needed other people to tell me that I was creative). It was almost a badge of honor that I couldn't wear unless someone else put it on me. I’m spiritual, a good friend, a good listener.

I was 9 when the genocide happened in Rwanda and I lost my whole family. We were here until the colonizers came and then they started dividing us – You have a long nose, you’re Tutsi. And then we started killing each other. A million people died in a hundred days. At age 11, I ended up on the street. But then someone became my dad. I met a man who asked, ‘What are you doing here?’ I said, ‘I live here’. And he straight up said, ‘Can I become your dad?’ I didn’t have a choice but that was the best ‘Yes’ I had ever done. He took me and gave me everything. He told me later, “I didn’t choose you because you were special. I chose you cause God told me to chose you. And if you get a life one day, just give back.” And that stuck with me. And then I met [my spouse] back at home and we moved here. A healer woman told me I would start something, a non-profit. And you will know the name. And then in 2015, Impanda came. Impanda means ‘a calling’ in my native language. So, I started going back and forth with Rwanda to pay health insurance for kids. It started with five kids and now we have 150 kids.

I moved here from Rwanda in September 2014. And it was totally different. At home, we had been colonized by the French and German so there were a lot of mixed kids. But I didn’t notice a problem with my skin until I moved here. With my accent and being black, I started feeling like, ‘Oooh’ (nodding). Moving here at age 29, leaving behind everything that you know, coming here to start over, it was really interesting. I worked so hard but there was something missing. There’s this silent treatment people give you that is really awful. I would rather it be to my face – ‘You’re a negro, we don’t like you’ instead of ‘Oh, we love you so much but we’re here to ignore you’. I call that the white savior

But I became depressed for four years. People were trying to help but it felt like white saviorism. Which was harmful for me even more, without them even noticing. That’s how ignorant the white privilege is. So, it did more damage. Sometimes they do it on purpose – as long as it serves them and they look good.

So, I went through a hard time. I had been trying to fit in but I felt empty and so lost until last year. And I realized I had a problem. The racism had gotten in my head. I was lost. Is there anything for me to do here cause everywhere I go, it feels like no one wants me. They ignore you. I didn’t feel like I belonged here, versus home where I knew everybody and everybody knew me.

So, I went to rehab, inpatient. I did 22 days detox and 9 weeks in-patient. I found myself again. I realized alcohol will never do it. But I realized why people go to alcohol or drugs, especially minorities. That’s how they center. White people will ignore you, make you so uncomfortable, make your life so hard, you will have to go use and then we can use what you’re using to say, “See? Look at you, using drugs. You’re a criminal.” I realized that in rehab when I saw a lot of natives and black people there.

Oppression divides minorities. It becomes a survival game. And when you are in a survival game, you can’t care about anyone else.

So, I went and did out-patient. And I thought, Okay I have to build Impanda up again… Now my purpose is to step up and speak for those who can’t speak for themselves. Activist against injustice. Activist against crime and all these things being done in the shadows. That’s what Dreaded Warrior is about….

I am….

…somebody who conquered. I am stronger than ever. I am a voice to those who can’t speak. I am the voice of peace but also of activism. I lead by action and I long to be truthful. If I’m not truthful to myself, then I won’t be truthful to others. I’m the son of God. I’m the son of all those brothers and sisters who have died

I moved here from Rwanda in September 2014. And it was totally different. At home, we had been colonized by the French and German so there were a lot of mixed kids. But I didn’t notice a problem with my skin until I moved here. With my accent and being black, I started feeling like, ‘Oooh’ (nodding). Moving here at age 29, leaving behind everything that you know, coming here to start over, it was really interesting. I worked so hard but there was something missing. There’s this silent treatment people give you that is really awful. I would rather it be to my face – ‘You’re a negro, we don’t like you’ instead of ‘Oh, we love you so much but we’re here to ignore you’. I call that the white savior

But I became depressed for four years. People were trying to help but it felt like white saviorism. Which was harmful for me even more, without them even noticing. That’s how ignorant the white privilege is. So, it did more damage. Sometimes they do it on purpose – as long as it serves them and they look good.

So, I went through a hard time. I had been trying to fit in but I felt empty and so lost until last year. And I realized I had a problem. The racism had gotten in my head. I was lost. Is there anything for me to do here cause everywhere I go, it feels like no one wants me. They ignore you. I didn’t feel like I belonged here, versus home where I knew everybody and everybody knew me.

So, I went to rehab, inpatient. I did 22 days detox and 9 weeks in-patient. I found myself again. I realized alcohol will never do it. But I realized why people go to alcohol or drugs, especially minorities. That’s how they center. White people will ignore you, make you so uncomfortable, make your life so hard, you will have to go use and then we can use what you’re using to say, “See? Look at you, using drugs. You’re a criminal.” I realized that in rehab when I saw a lot of natives and black people there.

Oppression divides minorities. It becomes a survival game. And when you are in a survival game, you can’t care about anyone else.

So, I went and did out-patient. And I thought, Okay I have to build Impanda up again… Now my purpose is to step up and speak for those who can’t speak for themselves. Activist against injustice. Activist against crime and all these things being done in the shadows. That’s what Dreaded Warrior is about….

I am….

…somebody who conquered. I am stronger than ever. I am a voice to those who can’t speak. I am the voice of peace but also of activism. I lead by action and I long to be truthful. If I’m not truthful to myself, then I won’t be truthful to others. I’m the son of God. I’m the son of all those brothers and sisters who have died

Ben (photographed with a traditional Filipino Jitney/Jeepney)

I went to an all-white school. They were making fun of my language, my accent, making fun of my appearance, my slanted eyes, everything. And they were young kids - in junior high school and high school. And they were always challenging me to go after school and fight, you know, those type of things. It was really tough. Even the teachers were racist or ignorant. There was really no understanding or even willingness to understand the issue of being Asian in this country or even understand the history. It was outright racist. My experience there, and also my experience in the military is the same thing: invisibility and exclusion. And even amongst the Filipino-Americans, I was Filipino-Filipino, ‘fresh off the boat’. And there were a lot of Filipino-Americans who were born here. They were always making fun of our accent, the accent of their parents. Many of those Asians, those Filipino Americans, related more closely to white people than Filipino-Filipinos.

There was a time where I hated myself. And I hated my parents for being Filipinos. Was that psychological impact of racism and exclusion? People want to be included. So, you start hating yourself because of the way you look, that you are not able to be included.

Being an activist – that really helped me out, really address that situation. I learned about our history here, the history of the Chinese Americans, the history of the Japanese Americans, the history of the Filipinos, so I'm aware that I'm not alone. There's been a whole history. And we had to really address that history, and fight against racism. And to do that, we have to unite with all the multi-ethnic communities to be able to do that. Because united with the multi-ethnic community you have the chance of fighting. I think that's one of the reasons why I stayed. I don't want our new generations to experience what we have experienced. I think that's basically one of the reasons why I continue to be an activist for so many years, since 1970.

I know in my heart that we belong to this country. And I fought for this country. I was in Vietnam for two years. I fought for the America that we believe in, which is America that is equitable and caring. I want that to come to realization. I want that to happen for our future generations.

I am…

a community organizer. That's who I am: community activist. I'm considered an elder. So, any issues that they face they call me. I get a lot of calls from referrals. I'm a go-to person. I still feel inadequate. But I feel I feel positive and hopeful.

I went to an all-white school. They were making fun of my language, my accent, making fun of my appearance, my slanted eyes, everything. And they were young kids - in junior high school and high school. And they were always challenging me to go after school and fight, you know, those type of things. It was really tough. Even the teachers were racist or ignorant. There was really no understanding or even willingness to understand the issue of being Asian in this country or even understand the history. It was outright racist. My experience there, and also my experience in the military is the same thing: invisibility and exclusion. And even amongst the Filipino-Americans, I was Filipino-Filipino, ‘fresh off the boat’. And there were a lot of Filipino-Americans who were born here. They were always making fun of our accent, the accent of their parents. Many of those Asians, those Filipino Americans, related more closely to white people than Filipino-Filipinos.

There was a time where I hated myself. And I hated my parents for being Filipinos. Was that psychological impact of racism and exclusion? People want to be included. So, you start hating yourself because of the way you look, that you are not able to be included.

Being an activist – that really helped me out, really address that situation. I learned about our history here, the history of the Chinese Americans, the history of the Japanese Americans, the history of the Filipinos, so I'm aware that I'm not alone. There's been a whole history. And we had to really address that history, and fight against racism. And to do that, we have to unite with all the multi-ethnic communities to be able to do that. Because united with the multi-ethnic community you have the chance of fighting. I think that's one of the reasons why I stayed. I don't want our new generations to experience what we have experienced. I think that's basically one of the reasons why I continue to be an activist for so many years, since 1970.

I know in my heart that we belong to this country. And I fought for this country. I was in Vietnam for two years. I fought for the America that we believe in, which is America that is equitable and caring. I want that to come to realization. I want that to happen for our future generations.

I am…

a community organizer. That's who I am: community activist. I'm considered an elder. So, any issues that they face they call me. I get a lot of calls from referrals. I'm a go-to person. I still feel inadequate. But I feel I feel positive and hopeful.

Tia (photographed at her college campus)

Kids, I think that they were really mean in school. For the most part I felt pretty welcome and safe in my schools, but there were kids who would say mean things like, "You'd better hide your dogs from her," or "Do you eat dogs," or "Ching chong ling long," while pulling the corners of their eyes.

I remember one time in [Mountlake Terrace visiting grandparents], we were trying to drive back to my auntie's house which was a few minutes away, and it was pretty late at night. This white elderly couple came by and it was really, really shocking and scary. They pulled up their phone and a flashlight and started recording my family. They started saying, “Go back to where you came from, you don't belong here”. And, “You're lucky this is a sanctuary city”.

I was just so appalled to be treated with such hostility, and they were trying to take pictures of our license plate. They said, “We're gonna report you guys”. And it was just really hard because this is my home. And my parents, they're citizens here but they've struggled through so much. With fleeing from a war, fleeing from Laos, because of the Secret War. And just to be treated with so much hatred and harassment when we were in a place that felt really safe for me like my grandparents’ home. It was really hard. And so my parents said, “Hurry get in the car, we just got to go”. Luckily they've never bothered us ever since and I still don't know who those people were, if they were neighbors or just passers by. I remember that moment very vividly, just feeling like a foreigner in my own home and feeling unsafe and that these people really don't want us here, don't think that we belong. That was like a hard feeling to grapple with.

I am....

an enthusiast, I love adventure. An optimist. A Hmong American woman.

I would say, a feminist, and a person who is actively trying to be anti-racist.

I wanted to be a US ambassador or a legislator for foreign policy because I do really care about immigration and immigrant rights. But, now, with the rise in anti-Asian hate crimes, I want to be an advocate for justice for Asian Americans.

I don't know what yet, but I know definitely now, especially with the stop Asian hate movement, something about Asian American rights

Kids, I think that they were really mean in school. For the most part I felt pretty welcome and safe in my schools, but there were kids who would say mean things like, "You'd better hide your dogs from her," or "Do you eat dogs," or "Ching chong ling long," while pulling the corners of their eyes.

I remember one time in [Mountlake Terrace visiting grandparents], we were trying to drive back to my auntie's house which was a few minutes away, and it was pretty late at night. This white elderly couple came by and it was really, really shocking and scary. They pulled up their phone and a flashlight and started recording my family. They started saying, “Go back to where you came from, you don't belong here”. And, “You're lucky this is a sanctuary city”.

I was just so appalled to be treated with such hostility, and they were trying to take pictures of our license plate. They said, “We're gonna report you guys”. And it was just really hard because this is my home. And my parents, they're citizens here but they've struggled through so much. With fleeing from a war, fleeing from Laos, because of the Secret War. And just to be treated with so much hatred and harassment when we were in a place that felt really safe for me like my grandparents’ home. It was really hard. And so my parents said, “Hurry get in the car, we just got to go”. Luckily they've never bothered us ever since and I still don't know who those people were, if they were neighbors or just passers by. I remember that moment very vividly, just feeling like a foreigner in my own home and feeling unsafe and that these people really don't want us here, don't think that we belong. That was like a hard feeling to grapple with.

I am....

an enthusiast, I love adventure. An optimist. A Hmong American woman.

I would say, a feminist, and a person who is actively trying to be anti-racist.

I wanted to be a US ambassador or a legislator for foreign policy because I do really care about immigration and immigrant rights. But, now, with the rise in anti-Asian hate crimes, I want to be an advocate for justice for Asian Americans.

I don't know what yet, but I know definitely now, especially with the stop Asian hate movement, something about Asian American rights

Sarah (photographed along a favorite trail)

I think it was in elementary school… the “Apu” jokes, things like that. But I didn't really internalize it, or I don't think I did. Whenever we'd be in public wearing our traditional Indian clothing, people would stare at you. I always felt uncomfortable doing that in public. So, whenever we had to dress up, we had to run an errand, I'd always be like, “Can I sit in the car?” Cause I just didn't like being stared at. So yeah, it was things like that that I didn't really process until I was away from home and learning different things and confronted with being “the only”. I had experiences like that back home, but I didn't really process it as being based on my identity until later.

Some of my cousins have accents and I don't. So, I was always trying to prove my Indian-ness in some situations and also blending in in others. My cousins, some of them thought, “Oh, but you're American. You're not Indian,” because I don't speak the language and I was born in the States. So, trying to grapple with that and wondering, why am I not Indian enough? Or, what does that mean being Indian and living out this identity? So, I was feeling kind of torn in that or just living in those two worlds. And often, as I got older, and became more vocal about my feelings and my beliefs, my dad would say, “You're too American now”. But then, conversely, “You're not Indian either”. So, those weird things where you're like, I don't know what it means to be Indian and what it means to belong in a family where we're all raised with different values and different experiences within different cultural contexts. So, all of that was just weird to grow up in and to figure out.

I still struggle with those Western expectations of what you should look like. And it's also interesting to think, a few years ago, it was having thin eyebrows and now it's, “We love thick eyebrows”. When you're a kid and you had traditionally thick eyebrows, you needed to pluck them or tweeze them, to make them look the way more European standards are. And it's resulted in me pushing back in terms of how white supremacy is so embedded in all of our cultures, regardless of whether we grew up in the US or not. And I see that a lot.

I am…

The daughter of Indian immigrants. Born and raised in Southern California. I often also use where I work as a descriptor. I think that is a huge part of my identity in terms of my values as a community organizer. I like to honor my parents’ immigrant story because that’s a huge part of who I am and how I have had the opportunity of becoming the person that I am today.

I think it was in elementary school… the “Apu” jokes, things like that. But I didn't really internalize it, or I don't think I did. Whenever we'd be in public wearing our traditional Indian clothing, people would stare at you. I always felt uncomfortable doing that in public. So, whenever we had to dress up, we had to run an errand, I'd always be like, “Can I sit in the car?” Cause I just didn't like being stared at. So yeah, it was things like that that I didn't really process until I was away from home and learning different things and confronted with being “the only”. I had experiences like that back home, but I didn't really process it as being based on my identity until later.

Some of my cousins have accents and I don't. So, I was always trying to prove my Indian-ness in some situations and also blending in in others. My cousins, some of them thought, “Oh, but you're American. You're not Indian,” because I don't speak the language and I was born in the States. So, trying to grapple with that and wondering, why am I not Indian enough? Or, what does that mean being Indian and living out this identity? So, I was feeling kind of torn in that or just living in those two worlds. And often, as I got older, and became more vocal about my feelings and my beliefs, my dad would say, “You're too American now”. But then, conversely, “You're not Indian either”. So, those weird things where you're like, I don't know what it means to be Indian and what it means to belong in a family where we're all raised with different values and different experiences within different cultural contexts. So, all of that was just weird to grow up in and to figure out.

I still struggle with those Western expectations of what you should look like. And it's also interesting to think, a few years ago, it was having thin eyebrows and now it's, “We love thick eyebrows”. When you're a kid and you had traditionally thick eyebrows, you needed to pluck them or tweeze them, to make them look the way more European standards are. And it's resulted in me pushing back in terms of how white supremacy is so embedded in all of our cultures, regardless of whether we grew up in the US or not. And I see that a lot.

I am…

The daughter of Indian immigrants. Born and raised in Southern California. I often also use where I work as a descriptor. I think that is a huge part of my identity in terms of my values as a community organizer. I like to honor my parents’ immigrant story because that’s a huge part of who I am and how I have had the opportunity of becoming the person that I am today.

James

My dad shared some things with me. Why he got in the service. Why he took his family from Kentucky all the way up here to Spokane. They called it the ‘red line’… they want the minorities in one place. My dad wanted to buy a house maybe 5 or 6 miles from where minorities, black people, had to stay. And over the phone, talking to the realtor, the talk was good. But then when they met, he said the house was sold.

Up here, it’s a little different. You know where you stand in the South. Up here, it’s a very passive type of racism. My dad didn’t talk to me much about it here. But in grade school there was a fight. Fifth and sixth graders. The principal called the police on these elementary kids. And as I was walking home, making my way through the alley, a police officer pulled out a gun on me. And I’m in the fifth grade. He pointed it at me and I just turned around and started running. When I got home, I told my mother about it and she said, “We can’t tell your dad”. So, fifth grade. That’s when I felt different.

…I kind of learned to expect the worst things. That helped me to prepare. That’s how I protect myself.

I am….

…a coach. I coached the fall sports. Spring sports. Then in the summer you had camps. I did football and track. Did basketball and did some wrestling. Conditioning and camps. I didn’t have time to have hobbies but I’m not complaining. I really enjoyed it. I had great kids and hopefully [I was] a mentor to them. Say positive things and they look up to you. But I been blessed doing it, almost 40 years doing it so I can’t complain.

I am really laid back. I appreciate what I have. I’m not too concerned with what I don’t have. Every morning I pray; I start out with the lord’s prayer every day. I talk to God and it helps me during the day. If anything comes up, I feel I have the strength to handle it.

My dad shared some things with me. Why he got in the service. Why he took his family from Kentucky all the way up here to Spokane. They called it the ‘red line’… they want the minorities in one place. My dad wanted to buy a house maybe 5 or 6 miles from where minorities, black people, had to stay. And over the phone, talking to the realtor, the talk was good. But then when they met, he said the house was sold.

Up here, it’s a little different. You know where you stand in the South. Up here, it’s a very passive type of racism. My dad didn’t talk to me much about it here. But in grade school there was a fight. Fifth and sixth graders. The principal called the police on these elementary kids. And as I was walking home, making my way through the alley, a police officer pulled out a gun on me. And I’m in the fifth grade. He pointed it at me and I just turned around and started running. When I got home, I told my mother about it and she said, “We can’t tell your dad”. So, fifth grade. That’s when I felt different.

…I kind of learned to expect the worst things. That helped me to prepare. That’s how I protect myself.

I am….

…a coach. I coached the fall sports. Spring sports. Then in the summer you had camps. I did football and track. Did basketball and did some wrestling. Conditioning and camps. I didn’t have time to have hobbies but I’m not complaining. I really enjoyed it. I had great kids and hopefully [I was] a mentor to them. Say positive things and they look up to you. But I been blessed doing it, almost 40 years doing it so I can’t complain.

I am really laid back. I appreciate what I have. I’m not too concerned with what I don’t have. Every morning I pray; I start out with the lord’s prayer every day. I talk to God and it helps me during the day. If anything comes up, I feel I have the strength to handle it.